One thing that is not in short supply in our working lives are potentially difficult conversations:

Giving or receiving feedback, selling ideas or proposals, being interviewed, performance appraisals, negotiations, contributing to meetings large and small, especially when the personalities of the participants can be so very different from one another. The list could go on. The point is that we are all faced with a multitude of occasions when we need to make our voices work in a particular way and where it can be difficult to ensure the outcome we would wish.

‘You look a bit stressed.’

‘Sure am. Got a difficult session coming up today.’

It’s an everyday occurrence.

What makes these conversations difficult is not just the uncertainty of the outcome, but the more immediate uncertainty of how the other person is going to react to what you say.

Unfortunately, we often fill this uncertainty with negative anticipations and self-limiting beliefs. ‘This isn’t going to be easy.’ ‘She’s got a reputation for being difficult.’ ‘I’m worried that my mind will go blank, when they start asking questions.’ ‘I don’t like having to confront people.’ ‘I can’t deal with all that touchy-feely stuff, when people want to talk about their worries.’ Again the list could go on and on.

The point is that there is no single, archetypal difficult conversation. Any conversation can be difficult, and it becomes a difficult conversation as soon as it feels like that to any of the people involved.

Which might be before, during or after the conversation itself, or indeed before, during and after. So the purpose of this blog is to provide a general framework for making meetings easier. You can use it beforehand to help you to prepare for what feels like a potentially difficult conversation, during the conversation itself to steer it in a productive direction, and after the event to reflect on it systematically, so that you can learn from the experience and handle other difficult conversations more easily in the future.

It’s a mystifying, but very common, human tendency not to prepare very carefully for potentially difficult conversations.

I’ve learned that lesson the hard way myself. Partly, I think, this is a result of how busy we all tend to be. But while that might be a cause, it certainly isn’t a good excuse for not preparing, and it probably isn’t the whole story either. Worrying about an impending difficult conversation tends to make us either procrastinate and put it off or to rush to get it over with. ‘I don’t know what I’m going to say, so I’ll just jump in and see what happens.’ Too slow or too fast, these are ways of exhibiting anxiety, not managing it, and neither helps to make a difficult conversation easier. Careful pacing does, especially during the conversation itself, but careful pacing starts with preparing beforehand.

Good preparation starts with the question, ‘What sort of conversation is this?’

At one level of course we will already have an answer to that question. It’s a sales pitch or a performance appraisal or a disciplinary interview or whatever. But we need to answer the question at a deeper level, to get beneath the label (which is probably fuelling our worries about it) and understand the different forces that are likely to be at work in a conversation of this sort.

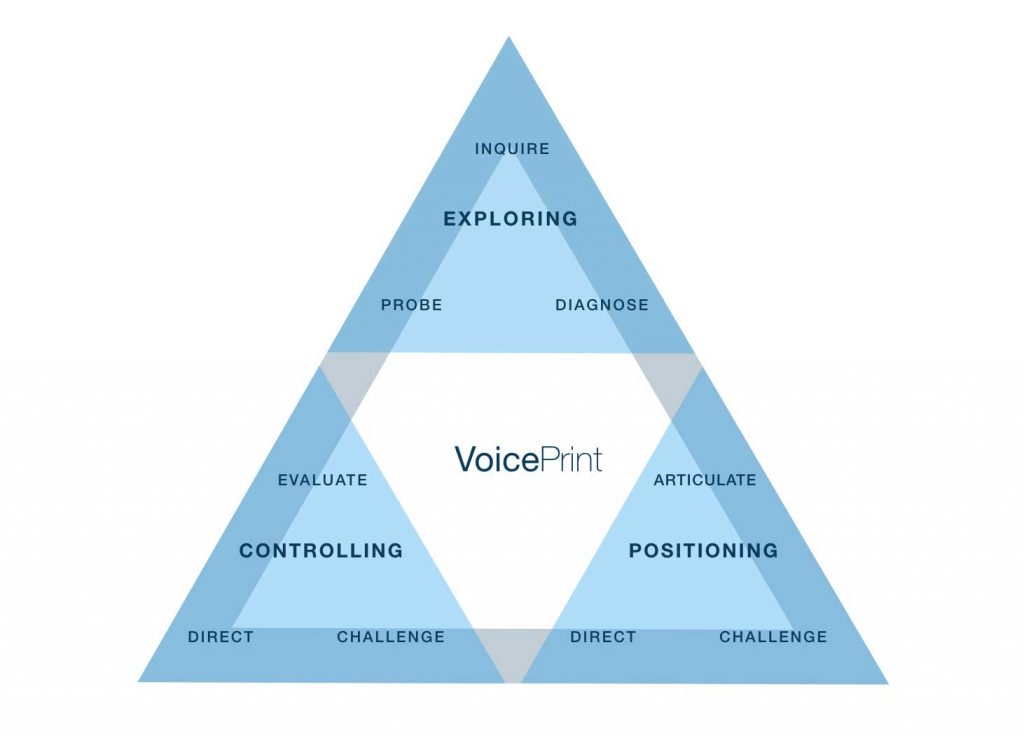

This is where the VoicePrint model provides a systematic framework for what is required in different types of conversation. It brings into conscious awareness the underlying structure of interactions and the pressures that pull people in different directions during these conversations. Once you have a grasp of these underlying dynamics, it becomes much easier to manage a difficult conversation, because you can use this awareness to recognise what is happening in the moment and to steer the conversation in productive directions and away from getting stuck in unproductive patterns.

The VoicePrint model is arranged around three angles which represent the three broad directions in which a conversation might need to go: towards exploring, positioning or controlling. Within this overall framework it then identifies nine distinctive ‘voices’ or ways of using talk, each of which serves a particular purpose. Different voices, and combinations of voices, are needed for different contexts and for particular types of conversation. Voices that are essential for one type of conversation might have limited value, or indeed be entirely counter-productive, in a different type of conversation.

In preparing for a potentially difficult conversation, the VoicePrint model provides a map of where to go and how to get there.

‘What voices does this conversation need?’ becomes the key question.

A sales pitch is certainly going to need the advocating voice at some point, but it’s also going to need the probing voice, if it’s to be based on a deep understanding of the customer’s needs. Performance appraisal is always going to involve the use of critique and ideally some advising. A disciplinary interview has to inquire open-mindedly and provide the opportunity for the interviewee to articulate, and it may or may not end up requiring the directing voice to provide a clear and explicit reminder about rules or responsibilities.

In each of these examples other voices may have a useful role to play too. The re-focusing effect of a timely and respectful challenge, for example, is particularly useful for keeping a conversation moving in a productive way. Inquiry without preconception is not only helpful in a general way to engage the other person/s in the conversation, but especially valuable in opening up new avenues when a conversation gets difficult, becomes stuck or starts to go round in circles. But in any particular type of conversation some voices will be essential.

Failing to use the voice that the conversation needs, when it needs it, is a sure-fire way of making it more difficult than it needs to be.

Recognising which voice a conversation needs and taking care to express yourself accordingly makes conversations not only easier, but also more effective and more productive.

If we only focus on what we want to achieve or say in a conversation, our preparation will be too one-sided. Of course we can’t know in advance exactly what someone else is going to say, or how the conversation will eventually turn out, even if we treat conversation at its most basic as taking turns to talk rather than adopting the more useful idea of it being an opportunity for jointly turning an issue over and re-examining it together. Nor can we tell our conversants what voices they should use. But we can invite others to use specific voices, especially when it would be helpful to make the conversation that we are having more productive. ‘If you were to critique what I’ve been proposing, what would your assessment be?’ ‘How would you summarise our discussion to articulate it for the people we need to report back to?’ ‘What issues do you want to probe more deeply at this point?’

There is an emergent quality to all conversations, an inevitable un-knowability about how they will turn out, but this does not mean that we cannot steer this interactive, co-creative process in useful directions.

It actually means that paying attention to steering conversations as they unfold is at least as important as working out what we want to say at the start. It’s a skill based on sensitivity and alertness to what is happening and what is required, in the moment and it’s a skill that most of us need to develop. It’s a fluid, dynamic capability that is qualitatively different from the ability to deliver an interesting presentation or to project oneself well at interview or any of the other essentially one-way forms of broadcasting that are often the subject matter of communications training.

Just as it takes two to do the proverbial tango, it takes two (or more) to converse. And it is the human dimension that complicates the process, because we vary so much in terms of our personalities and in the related diversity of how we use talk. Different people rely on different voices, combinations of voices and sequences for using their voices. The result is that when one individual converses with another, regardless of the particular type of conversation that they are engaged in, the two are already likely to be approaching the conversation is fundamentally different ways. Consequently they often find themselves talking at cross-purposes without realising it, misunderstanding each other’s intentions and becoming frustrated that the other person either ‘just doesn’t get what I’m saying’ or is being ‘deliberately difficult.’ The problematic nature of the whole business of conversing is further compounded by the fact that talking comes for the most part so naturally that we don’t give a lot of conscious attention to how we’re doing it. We just do it.

As long as we remain generally unaware of our idiosyncratic pattern of voices, our personal tendency to over-use some and under-use others, regardless of which might be most appropriate for the particular the of conversation we are in, the task of handling potentially difficult conversations will continue to be more difficult than it needs to be.

But this is where the VoicePrint framework can again prove useful in preparing for, conducting and reviewing your difficult conversations. The VoicePrint profiling tools can give you powerful insights into your distinctive ways of using the voices, the impacts that you are likely to have (both deliberate and unintended) and where you might need to develop your repertoire. Knowing your VoicePrint profile sheds light on both the unconscious intentions that you tend to bring with you into your conversations and the effects these are likely to have, without you realising it, when you get there.

Self awareness is the foundation not only for self-management but also for effective conversation management.

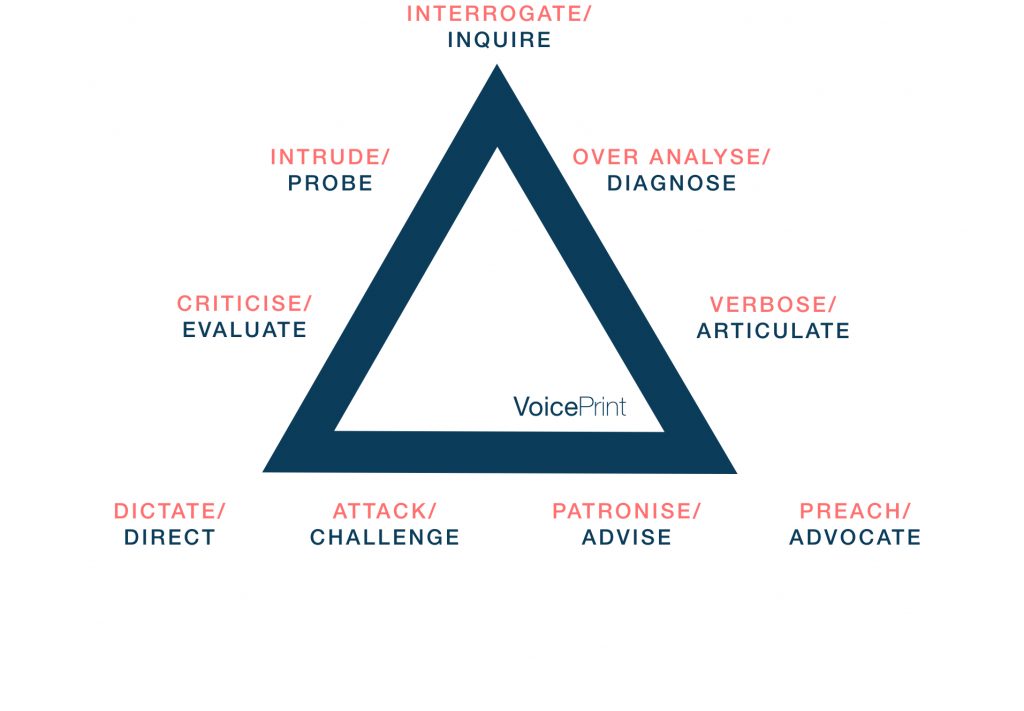

Look again at the VoicePrint model. This time we’ve highlighted how any voice can come across negatively, if it is used unskilfully, at the wrong time or simply for too long, when the conversation would benefit from a change of direction. You can use this to make sense of your own and your conversants’ behaviours and reactions, and to keep steering your conversations in the directions that will make them easier and more productive.

SUMMARY

7 Steps for Handling Difficult Conversations

- Decide what particular voices this particular type of conversation needs.

2. Know your own talking tendencies; use the voices that the conversation needs rather than unconsciously relying on the voices that you characteristically tend to employ.

3. Know your own sensitivities; recognise which voices tend to trigger a negative response in you; put your reflex reactions on hold; take the time to understand what your conversant wants to get across to you.

4. Look out for your conversant’s sensitivities; you’ve got some, they’ll have some too, although they may not be the same as yours; notice when your intention does not match your impact; adjust your voice to make the conversation work.

5. Prepare carefully before potentially difficult conversations, but only to the extent that it is possible to prepare for what is an interactive process.

6. Review thoughtfully after any conversation that felt difficult; ones that have gone really badly, and we’ve all had some of those, are the ones from which we can learn most about how to handle difficult conversations more easily and better.

7. Take an active role in steering your conversations as they unfold in real time; they don’t steer themselves; facilitate them. That’s what facilitation means – to make easier. That’s exactly what difficult conversations need.

Alan Robertson